Federal protection of endangered species dates back to the Lacey Act of 1900, when Congress passed the first wildlife law in response to growing public concern over the decline of the passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius). The Lacey Act prohibited interstate commerce of animals killed illegally and required the secretary of agriculture to preserve, introduce, distribute, and restore wild bird and game bird.

As public awareness of environmental problems initiated political activism in the 1960s, the Department of Interior formed a Committee on Rare and Endangered Wildlife Species to identify species in immediate danger of extinction.

The Redbook on Rare and Endangered Fish and Wildlife of the United States, published in 1964, served as the first official document listing species the federal government considered to be in danger of extinction. Two years after the Redbook list was published, Congress passed the Endangered Species Protection Act of 1966—the first piece of comprehensive endangered species legislation.

The goal, as stated in the 1966 Act, was to "conserve, protect, restore, and propagate certain species of native fish and wildlife." It was under the 1966 Endangered Species Preservation Act that the very first list of threatened and endangered species was created,

There are more than a thousand listed - see

http://ecos.fws.gov/tess_public/pub/listedAnimals.jsp

Some are well known to the public and others are largely unknown. Here are some mammal examples

Indiana Bat - Myotis sodalis

Delmarva Peninsula Fox Squirrel - Sciurus niger cinereus

Timber Wolf - Canis lupus lycaon

Red Wolf - Canis niger

San Joaquin Kit Fox - Vulpes macrotis mutica

Grizzly Bear - Ursus horribilis

Black-footed Ferret - Mustela nigripes

Florida Panther - Felis concolor coryi

Caribbean Monk Seal - Monachus tropicalis

Guadalupe Fur Seal - Arctocephalus philippi townsendi

Florida Manatee or Florida Sea Cow - Trichechus manatus latirostris

Key Deer - Odocoileus virginianus clavium

Columbian White-tailed Deer - Odocoileus virginianus leucurus

Sonoran Pronghorn - Antilocapra americana sonoriensis

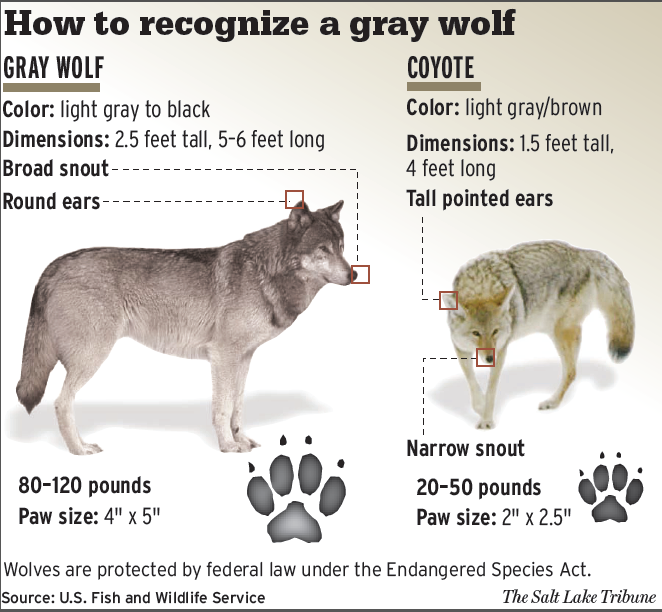

The Gray Wolf, (Canis lupus), is a good example of a species that is both loved and mythologized by the general public, but also seen as a nuisance predator by some farmers and ranchers.

It is a "keystone predator," and is an integral component of the ecosystems to which it typically belongs. The wide range of habitats in which wolves can thrive reflects their adaptability as a species, and includes temperate forests, mountains, tundra, taiga, and grasslands.

Gray wolves were originally listed as subspecies or as regional populations of subspecies in the contiguous United States and Mexico. In 1978, they were reclassifed as an endangered population at the species level (C. lupus) throughout the contiguous United States and Mexico, except for the Minnesota gray wolf population, which was classified as threatened. (Gray wolf populations in the Northern Rocky Mountains and Western Great Lakes were delisted due to recovery in 2011 and 2012)

Each state has its own unique list of species that are federally protect and exist in that state, and also species that are listed as threatened or endangered in that state but not across the country. (See the NJ list at

state.nj.us/dep/fgw/tandespp.htm)

The general public often doesn't realize that listings include not only mammals but also birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes, insects and

plants.

An example of the plants is the

NJ Swamp pink (Helonias bullata.

Swamp pink was federally listed as a threatened species in 1988.

A perennial member of the lily family, swamp pink has smooth, oblong, dark green leaves that form an evergreen rosette. In spring, some rosettes produce a flowering stalk that can grow over 3 feet tall. The stalk is topped by a 1 to 3-inch-long cluster of 30 to 50 small, fragrant, pink flowers dotted with pale blue anthers. The evergreen leaves of swamp pink can be seen year round, and flowering occurs between March and May.

Supporting over half of the known populations, New Jersey is the stronghold for swamp pink. Swamp pink occurs in Morris, Middlesex, Monmouth, Ocean, Burlington, Camden, Gloucester, Atlantic, Salem, Cumberland, and Cape May Counties.